It is worthwhile at this point in the series to revisit Göbekli Tepe, a Neolithic monument complex in southeastern Turkey, to see if the previous 20+ posts can shed any light on its rise and fall. I facetiously labelled the post on Göbekli Tepe “I ain’t no student of ancient culture. Before I talk, I should read a book” as I, like the B-52s and most everyone else, am almost certainly inadequately qualified to write a post on the rise of human civilization. But I feel that membership has its privileges, so I’d like to give it a try. This post should however be treated with some degree of skepticism: readers are encouraged to do their own research, make their own reasonable assumptions, draw their own reasonable conclusions, and if need be write their own reasonable substacks.

What is a civilization?

Thick, ponderous tomes have been written about what constitutes a civilization, yet the definition of the word still leaves something to be desired. Brittanica:

the condition that exists when people have developed effective ways of organizing a society and care about art, science, etc.

They had me until the word “etc.”. Clearly anything before an “etc.” cannot be a requirement, so what remains is “an effective way of organizing a society”. Which I feel is too low a bar as a master whose every whim is catered to by 100 slaves can also be a highly effective way of organizing a society. But is hardly civil.

The definition has bedevilled the numerous archeologists and anthropologists debating the issue, and usually at a certain point is punted to a “we can’t define it, but we’ll know it when we see it” definition. Clearly a line must be arbitrarily drawn somewhere. Conceding that civilization is a human condition, i.e. that animals aren’t civilized, and that an animal’s main objective is a biological one, i.e. survive long enough to procreate, then a low bar could be set at a society that does more than just eat, sleep and have sex. We (and Brittanica) intuitively feel that a civilized society has to do more than behave like animals, that is care about more than just survival, so have enough leisure time to care about “art, science, etc.”. Therefore this post will use as a working definition: a civilization is a society that has sufficient leisure time - time not associated with survival - that is used to help other members achieve a more meaningful and pleasurable life experience. Which still leaves the question on what is “pleasurable” or “meaningful” to which I reply: I won’t define it but I’ll know it when I see it.

Abu Hureyra and the Natufians

Abu Hureyra (AH) was an important pre-historic mound settlement in Northern Syria that was excavated via a set of trenches just before the area was flooded by Lake Assad in 1973[1]. The original team of archeologists[1] determined that the village had been continuously occupied between ~11,500 to ~7,000 BP (14C age), but that the main occupation periods were between ~11,500 to ~10,000 BP (AH1) and between ~9,400 to 7,000 BP (AH2). Converting these to cal ages previously used in this series:

AH1: 13.5 - 11.4 ka

Intermediate Period: 11.4 - 10.6 ka

AH2: 10.6 - 7.8 ka

The AH1 population was small, probably only a few hundred people at most, but at the time (13.5 ka) could have been Earth’s largest permanent dwelling. Inhabitants built small round huts over hearths and food storage areas cut into the soft sandstone[1].

A different Abu Hureyra origin story

AH1 was originally settled by a group of hunter-gatherers that pre-AH1 very likely intermittently made camp on this small hill overlooking the Euphrates in order to forage in the AH area. The classic origin story is that these “Natufians” progressively spent more and more time in their camp until the day they decided that local food resources were sufficient to settle there permanently. A large part of any decision to settle however must have been based on their ability - technology - to conserve and store meat, fruit and grain: by settling there they effectively became “hunter-collectors", as they didn't only gather food for immediate consumption, but also for the winter months when the local food supply was insufficient.

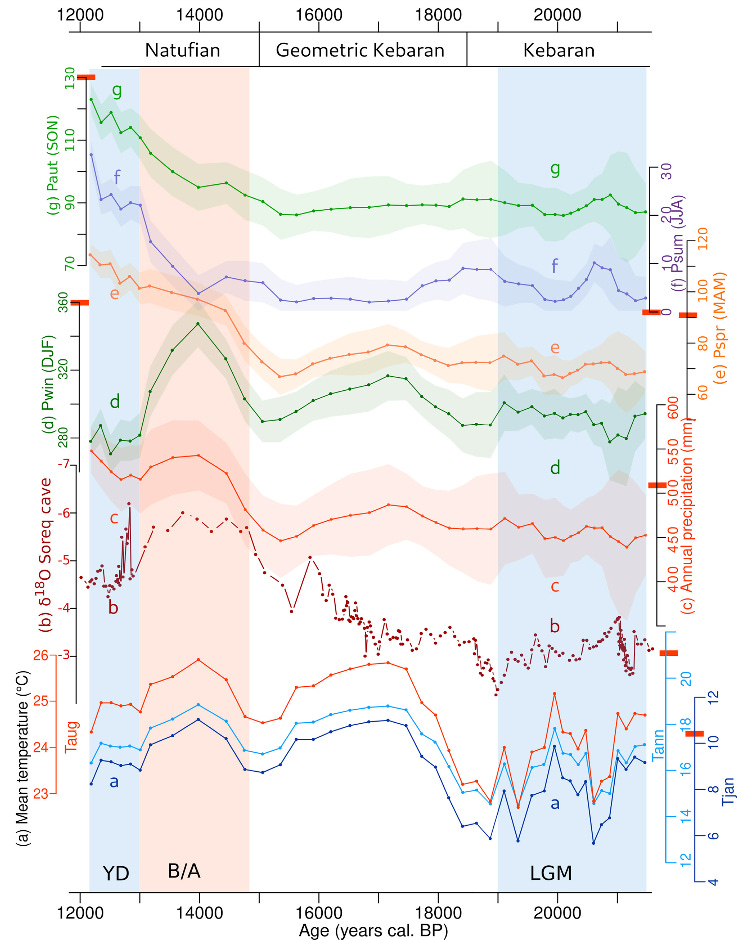

This post proposes a different origin story. The fairly detailed Jordan River Dureijat (JRD) paleoclimate model can be used as a proxy for the climate at Abu Hureyra, although JRD very likely had a more Mediterranean climate and AH a more Continental climate: precipitation was probably lower at AH in general, while its summer and winter temperature extremes were likely larger. At the start of the Bølling-Allerød (14.7 ka) the temperatures and rainfall started to increase in the Levant. This heralded a great period to be a hunter-gatherer, with ever-increasing food supplies and - with more people surviving to the age of procreation - ever-expanding tribe populations. This happy time very likely (partially) ended around the start of the Older Dryas (14.05 - 13.9 ka) when the regional temperatures started to drop again and winter rainfall started to decrease. The graphs above don’t reflect the severe Older Dryas temperature changes of the Greenland ice cores, nor the return to Arctic tundra-like conditions in much of Europe, but for a few hundred years the Natufian hunter-gatherers very likely got a taste of worse things to come, so started to learn - the hard way - about how to have enough to eat during winter by learning how to effectively store food for periods when food supply was low. Their settlement of Abu Hureyra around 13.5 ka roughly coincides with the 13.3 ka climate change event, which very likely caused a new sharp reduction in winter food supply. The earliest AH1 huts had food storage spaces dug into the sandstone bedrock, indicating that by ~13.5 ka they had mastered this technology.

AH1 was therefore very likely settled in response to climate change. The validity of this alternate origin story is demonstrated by the fact that the Abu Hureyra hunter-collectors successfully survived the Younger Dryas - an even more severe climate change event - while traditional hunter-gatherer communities very likely were decimated during winters. It is further validated by the fact that the large exodus from the village that initiated the “Intermediate Period” occurred around 11.4 ka, ~300 years after temperatures, rainfall and food supplies started to increase again during the early Holocene, that is during times when food the supply was increasing again. AH1 was settled in response to “tough times”.

Was AH1 “civilized”?

Though there’s much to admire about the scrappy Natufians that banded together to survive the Younger Dryas (YD), the working definition above indicates they did not qualify as a civilization. They effectively organized their society and survived the YD, so can pass the lowest bar, but there’s little to suggest they cared about the “arts, sciences, etc.”. Their tools were largely functional, the AH1 inhabitants had little to aspire to other than to survive until procreation, and there’s no evidence future civilizations benefitted from their cultural advancements

But it’s a close call. Moore et al.[1] mention the AH1 inhabitants did care for the weaker members of their society: there’s evidence that a girl who suffered a crippling back injury in her youth was taken care of and lived to be a mature woman. There’s evidence they dabbled in agriculture and animal husbandry, though the full societal benefits didn’t occur until AH2B around 9.3 ka. The main AH1 achievement was to survive the YD, that is to eat, sleep and procreate for ~2000 years.

The development of agriculture

One of the key questions that has been tormenting archeologists for decades is: which came first, the settlement or the agriculture. In other words, did the advent of agriculture force hunter-gatherers to stay in one place, or did the hunter-gatherers staying in one place force them to develop a constant food supply through agriculture? The answer above is: neither, climate change forced both.

During early Bølling-Allerød (BA) times there was no need to put a lot of effort into cultivating or storing food, as food was plentiful. But growing populations and worsening climate would have caused major survival concerns. New technology is often developed to meet an urgent need, in this case surviving the long periods of low food supply during the late BA and YD. The AH1 inhabitants started dabbling in rye cultivation around 13 ka[5], likely experimenting with ways to increase food supply. Apparently the need was not so great or urgent that growing rye was worth a major effort: there is little evidence that crop cultivation and animal husbandry had a significant impact on the AH inhabitants’ hunter-collector lifestyle until AH2B around 9.3 ka[1]

The Taş Tepeler culture

Around the same time Natufians were settling Abu Hureyra the Taş Tepeler people were settling Karahan Tepe (KT), whose oldest remains (so far) date back to 13 ka, i.e. well before the founding of Göbekli Tepe’s (oldest) Enclosure D around 11.5 ka.

There are a number of similarities with Abu Hureyra:

KT’s inhabitants were mainly hunter-collectors, who may have dabbled in crop cultivation

They stored their food, indicating they likely founded KT for similar (climate change) reasons, i.e. during a period when (winter) food supplies were no longer achievable through local foraging.

But the similarities end there. Only secular structures were unearthed at AH, i.e. dwellings, while the KT inhabitants created both sacred and secular structures. A KT visitor’s attention is immediately drawn to what has been referred to as “the penis chamber” or “snake pit”, an enclosure of tall pillars in front of a large, carved, anthropomorphic head that somewhat resembles a snake. I was immediately awed and fascinated by the pit and reflected: “It must have been quite a show” to the person standing next to me. I imagined - fancifully - a water filled enclosure and a hopped-up priest dancing from pillar to pillar in an attempt to placate the menacing and unforgiving snake-god. I’d pay good money to see that and so would anyone.

Does Karahan Tepe qualify as a civilization? Yes!

Göbekli Tepe

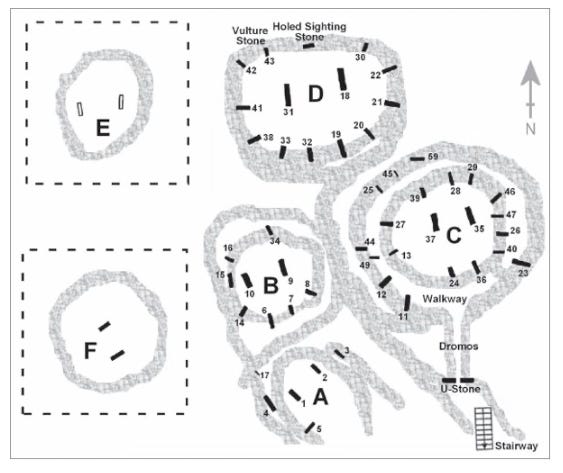

The Göbekli Tepe (GT) monumental complex consists of a number of oval enclosures containing upright limestone megaliths (slabs). Many of these slabs are decorated with low and high relief zoomorphic and anthropomorphic pictograms, and have upper T-shaped terminations (T-pillars). The oldest and most complex enclosure, Enclosure D, has been reliably dated to 11,530 BP ± 220 years, indicating that the complex was very likely founded after the Younger Dryas.

Though some dwellings have recently been found at GT, the site is ill-suited for permanent habitation: the nearest water-source is ~5 km away[6] and it sits on top of a high hill that presumably was remote from foraging locations. But as a site for a monumental complex it’s hard to beat. The main requirement for the site was likely a clear, unobstructed view to the southeast, the direction in which the enclosures are open, the paleodirection of Orion at the summer solstice. The nearby availability of construction materials, i.e. limestone quarries, was either a happy coincidence or a secondary requirement.

It’s hard not to feel awed and menaced by the enclosures’ decorated pillars that depict snarling boars, foxes, large cats, etc. Once again I thought it would be a great place for a hopped-up priest and some naked virgins to put on a religious ceremony. I would have gladly joined their cult and civilization just to watch the show.

Did an early cycle of civilization transfer agricultural technology?

A major point of disagreement among archeologists is what happened to human civilization in the years between the demise of Göbekli Tepe around ~10 ka and the rise of the Sumerian civilization - the first commonly recognized “earliest” civilization - around 7.5 ka. This period generally coincides with the rise of agriculture (“Neolithic Revolution”, “First Agricultural Revolution”, etc.) that started around 12 - 10 ka.

Some alt-archeologists (Graham Hancock, Robert Schoch, etc.) have also joined the fray, suggesting that a technically-advanced, pre-Holocene civilization that was wiped out by some catastrophe transferred agricultural knowledge to the Neolithic hunter-gatherer community, but there’s scant evidence supporting this theory and much evidence disproving it. Not to pick favorites, but Robert Schoch’s “Solar-induced Dark Age” (SIDA) is further discussed here, as it can easily be compared to data presented in previous posts. His theory is that a huge “solar outburst” (a solar particle event) around the end of the Younger Dryas (11.7 ka) terminated an “early cycle of civilization”, and threw humanity literally back into the stone age. His proposed SIDA lasted from 11.7 ka to ~6-5 ka, but relies on a rather inconsistent timeline[7], as “early cycle” Göbekli Tepe was evidently founded after his solar event and Sumer was founded ( ~7.5 ka) during his SIDA by “West Asian” people, who very likely were experienced farmers. Also, the adoption of crop cultivation and animal husbandry was a gradual, evolving technology at Abu Hureyra, that is to say a very slow-moving revolution, whose progress was likely driven by need and not “early cycle” revelation. In addition, the previous post demonstrated the Late Pleistocene “catastrophic” extinction mainly decimated the American and Australian megafauna long before 11.7 ka, but largely spared Levant and Asian fauna due to the relatively high geomagnetic field strength over these areas. For example, there is no evidence of a significant diet change at AH1 or KT due to a faunal or floral extinction.

The rise and fall (AH1) and rise and fall (AH2) of Abu Hureyra

While the following “human civilization” reconstruction is speculative, it does fit all the facts concerning the domestication of crops and animals, the transition from the foraging, nomadic lifestyle to the settled, agricultural lifestyle via the hunter-collector lifestyle, and the numerous climate change events between 13.5 - 7.5 ka.

During the Late Bølling-Allerod the Natufians and Taş Tepelers settled Abu Hureyra and Karahan Tepe respectively, very likely in response to climate change: the colder, dryer winter months were very likely causing starvation among the hunter-gatherer communities, prompting an urgent need for food storage technologies that enabled survival. The settlers demonstrably had developed technologies that enabled them to remain year-round in one (choice) food storage location at their times of settlement: the hunter-gatherers became hunter-collectors. They dabbled in and partially succeeded with new cultivation technologies to increase their stored food supply, such as cultivating rye, but still needed to mainly rely on foraging: it was food storage technologies, not agriculture that enabled their survival of the Older and Younger Dryas climate change events.

During the early Holocene the climate became warmer and wetter, and food became relatively abundant again. Populations very likely increased, as would have leisure time, as less manpower would have been required to hunt-collect food. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle became a viable option again, although after ~2000 years of settlement there was very likely no great need or wish to return to the nomadic lifestyles of the past. Any urgent need for agriculture was very likely diminished by the relative abundance of food. The AH and KT populations responded to these improved circumstances differently. The Taş Tepeler population founded a monumental complex at Göbekli Tepe, at a central location between their villages, very likely to travel there for joint celebrations at special occasions, e.g. the summer solstice.

Most of the AH1 inhabitants had abandoned their village by ~11.4 ka[1] (a small group remained) at a point in time when the “tough times” had been over for ~300 years. It is therefore very likely that they weren’t forced to leave or died out, but rather chose to leave to a more attractive location. They might have gone to Mureybet, roughly 30 km upriver, but why would they consider this highly similar village more attractive? Mureybet at the time could pass for an AH1 clone: secular buildings, dabbling in crop cultivation and animal husbandry, an uncivilized eat, sleep, and procreate community.

The AH and KT communities very likely knew of each other’s existence: building and tool materials found at AH came from a very large source area. Göbekli Tepe is roughly 150 km away from AH, so too far for AH inhabitants to join cultural celebrations there, but not so distant that some residents couldn’t move to the neighborhood. The AH “intermediate period” roughly coincides with the rise and fall of Göbekli Tepe, so a (speculative) theory is that the AH1 community wanted to move closer to “civilization”, in a manner similar to latter-day farmers moving to the big city in search of a more meaningful and pleasurable existence. I would.

Göbekli Tepe was permanently abandoned and purposely buried/decommissioned around 10 ka, but had already been in decline for a long period by then: the later enclosures, e.g. Enclosure A, became progressively smaller and less decorated.

Around 10.6 ka the AH2 phase of Abu Hureyra started, suggesting its inhabitants returned from wherever they had been for the past 800 years. The new inhabitants showed evidence of having picked up some new tricks[1]: the cultivation of mountain goats and sheep, a new style of mudbrick house building, the cultivation of some new varieties of grain, etc. But it wasn’t until AH2B (9.3 - 8.1 ka) that a noticeable dietary shift happened, signalling the full transition to an agricultural community, whereby the population expanded from ~2500 (AH2A) to 5000-6000 (AH2B)[1]. The population declined again during AH2C to ~2500, but the end of AH2C (~7.8 ka) roughly coincides with the rise of Sumer (~7.5 ka), so perhaps by 7.8 ka a large number of AH2C inhabitants were moving downstream to start a new, exciting civilization. Although such a theory is speculative, the “West Asian” famers who started Sumer very likely came from the largest villages in the “Fertile Crescent” in West Asia, e.g. Abu Hureyra. They had mastered agriculture and would have found southern Mesopotamia a highly desirable, easy place to survive, a place where a Natufian would have sufficient leisure time to start a new civilization.

What happened between 11.7 ka and 7.8 ka?

In a nutshell, mainly climate change. North American climate reconstructions[8] demonstrate abrupt cooling periods around 10.6 ka, 10.2 ka, 9.6 ka, 9.2 ka, 8.8 ka, and 8.4 ka that concur with the AH2 resettlement period. Many of these events are also recognized in the global climate record, so most are very likely large regional or global climate change events. The authors[8] suggest these cooling events are the result of a weakening Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). The last of of the events almost concurs with the 8.2 ka cooling event noticeable in Greenland ice core temperature proxies, and was very likely caused by the final emptying of Lake Agassiz into the North Atlantic via Hudson Bay. Greenland ice core temperature proxies show a fairly monotonous temperature increase after the YD, so any climate change was very likely not caused by an expansion of North Atlantic sea ice cover. However the formation of a North Atlantic Low Density Water Mass that disrupted the AMOC, in a manner similar to the Older Dryas, the 13.3 ka event, and the YD, is very likely. Global sea levels rose an additional 60 m after the YD, indicating large volumes of Laurentian ice sheet meltwaters were still entering the North Atlantic between 11.7 and 8.2 ka. These large meltwater pulses would have almost certainly temporarily overwhelmed the AMOC, in a manner similar to the BA and YD analogues, periodically causing colder, drier climates in Europe and the Levant that were survivable thanks to the adoption of hunter-collector and agricultural lifestyles. Arts, science, and civilization often had to be put on the backburner in favor of survival.

The concurrence of the first major post-YD cold, climate change events with the resettlement of Abu Hureyra and the advent of AH2 agriculture is highly suggestive: it suggests this village was a convenient place to weather out the severe climate change episodes that would have caused mass starvation in any hunter-gatherer community. It suggests that agriculture was necessary to weather such low food supply periods. It is therefore very likely that a large part of the Taş Tepeler population moved to areas, such as the Euphrates valley and southeastern Europe (e.g. Lepenski Vir), that were more suitable to an agricultural lifestyle in order to survive until the Holocene climatic optimum (~8 ka).

Summary

The Abu Hureyra village was at the cross-roads of early civilizations and provides the key to understanding humankind’s transition from hunter-gatherer to farmer. The village was very likely settled during the Late Bølling-Allerød, when periods of relative cold and dry climates (e.g. Older Dryas) forced hunter-gatherers to re-think their survival strategies by storing food for periods when supply was low: they became hunter-collectors. This necessitated dwelling permanently near their main storage sites, e.g. Abu Hureyra, Karahan Tepe, etc. During the early Holocene the climate became warmer and wetter again, and food supply became less of an issue, which very likely prompted many Abu Hureyra inhabitants to leave their dull and unexciting village, speculatively to join the Neolithic party at Göbekli Tepe. Two cold, dry climate events that occurred between 10.6 ka - 10.2 ka very likely forced the Abu Hureyra inhabitants to return to their village and transition to an agricultural lifestyle of crop cultivation and animal husbandry in order to survive “tough times”. The Holocene Climate Optimum around 8 ka was very likely the start gun for the “Fertile Crescent” inhabitants to once again leave their dull, unexciting, uncivilized villages in order to start a new civilization at Sumer.

The rise of civilization can thus be summarized as:

13 - 10 ka: rise and fall of the Taş Tepeler hunter-collector civilization

10 - 8 ka: collapse of hunter-collector civilization due to climate change

8-5 ka: rise of the Sumer agricultural civilization

References

[1] Moore, A., Hillman, G., Legge, A., 2000, Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510806-X.

[2] Pavón-Carrasco, F.J., Osete, M.L., Torta, J.M., De Santis, A., 2014, A geomagnetic field model for the Holocene based on archaeomagnetic and lava flow data, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 388, 98-109, //doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.11.046.

[3] Dafna Langgut, D., Cheddadi, R., Sharon, G., 2021, Climate and environmental reconstruction of the Epipaleolithic Mediterranean Levant (22.0–11.9 ka cal. BP), Quaternary Science Reviews, 270, 107170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.107170.

[4] Willcox, G., Buxo, R., & Herveux, L., 2009, Late Pleistocene and early Holocene climate and the beginnings of cultivation in northern Syria. The Holocene, 19, 151-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683608098961

[5] Hillman, G. et al., 2001, New evidence of Late Glacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates. Hol., 11(4), 383-. 10.1191/095968301678302823.

[6] Collins, A., 2014, Göbekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods: The Temple of the Watchers and the Discovery of Eden. Bear & Company, pp 464. ISBN: 978-1591431428

[7] Schoch, R., 2021, Forgotten Civilization: The Role of Solar Outbursts in Our Past and Future. Inner Traditions, 2nd ed., 560 pp. ISBN: 978-1644112922

[8] Hou, J. et al., 2012, Abrupt cooling repeatedly punctuated early-Holocene climate in eastern North America. Holocene, 22, 525-529. 10.1177/0959683611427329.